Medical Pioneer: Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell

Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell

Scalpel ... Stethoscope ... Gauze ... Iron Will

Could you imagine a world with no female doctors? Or one that denies women the ability to learn medicine because they’re considered intellectually inferior? We could be living in that kind of world if it wasn’t for Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, America’s first female doctor.

Born February 3, 1821 in Bristol, Gloucestershire, England, Elizabeth was the third daughter of sugar refiner Samuel Blackwell and his wife Hannah. The Blackwell family was immense with nine children—Anna, Marian, Elizabeth, Samuel (who later married suffragist, abolitionist and first female minister ordained in the United States Antoinette Brown), Henry (who later married women’s rights activist Lucy Stone), Emily, Sarah, John and George.

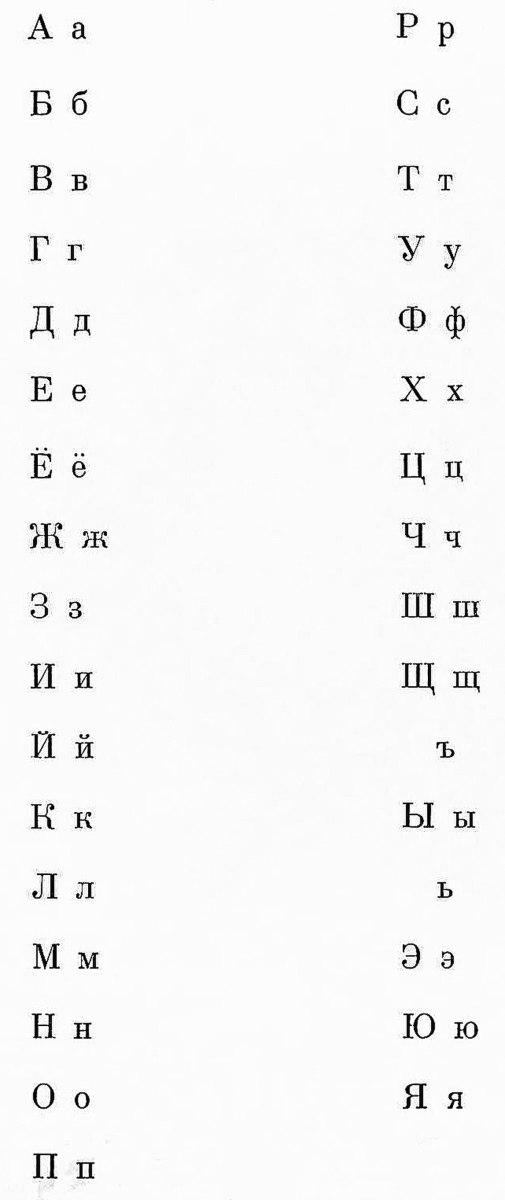

Mr. Blackwell was rather enlightened for his time, and he demanded only the best education for every one of his children—that’s daughters as well as sons. Elizabeth was assigned a governess and tutors in subjects such as literature, math and languages. Elizabeth spent so much time studying that she rarely went outdoors, and as a result became quite isolated, never developing much of a social life as a young girl.

Things changed rapidly for the Blackwell family, and not in an especially good way; following the British government’s rejection of the second Reform Bill, which would have given Bristol and several other industry-based towns greater representation in government, violent riots broke out in 1831. Alarmed for the safety of his family and his business, Mr. Blackwell quickly gathered up his wife and children and moved to the United States, where things were calmer … for a little while. Settling in New York, Mr. Blackwell set up the Congress Sugar Refinery in New York City, and soon became involved in the abolitionist movement and social reform. He became friends with notable abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison and Theodore Weld, and his involvement in the movement motivated all of his children so much that they actually boycotted sugar to protest slavery.

Then, the unthinkable happened in 1836—the Blackwells’ sugar factory caught fire and burned to the ground. Mr. Blackwell rapidly rebuilt the factory, but he was never able to recoup his losses. Ultimately, he gathered his family up again and moved them to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he established a new sugar business and planned on experimenting with sugar beets, which, unlike cane sugar, did not require slave labor. Tragically, Mr. Blackwell never had the chance to try his new business—he died three weeks after arriving in Cincinnati from illness, leaving Hannah and their nine children deeply in debt.

Acting swiftly, the three eldest daughters—Anna, Marian and Elizabeth—established the Cincinnati English and French Academy for Young Ladies. Teaching in itself didn’t bring in much money, so the three sisters charged for tuition, room and board to make up the costs. At the time, teaching was really the only acceptable profession for an educated woman though it didn’t pay well, and since any money they made would go straight to their husbands, they never married (as it turns out, not one of the Blackwell daughters ever married.)

Always intellectually and spiritually restless and fiercely independent, Elizabeth converted to Episcopalian in December, 1838. She wasn’t there long; shortly after converting, Elizabeth met controversial William Henry Channing, a leading figure in the practice of transcendentalism (the belief that humanity inherently good and that organized religion had become corrupted), and was so taken by his speeches that she joined the Unitarian church. All she was looking for was spiritual enlightenment, but a scandalized Cincinnati didn’t see it that way and her pupils were rapidly pulled from her school. The Blackwells lost so many students that they were forced to close the Academy in 1842.

Still in need of money, Elizabeth took up a teaching job in the then-backwater town of Henderson, Kentucky. While she liked her students, Elizabeth couldn’t stand the living conditions or the people she had to deal with, or the fact that now she had to stare slavery in the face every day, as Kentucky permitted it. Frustrated, Elizabeth returned home after a year, unsure of what she wanted in her life, feeling unhappy with everything she had done up to that point.

Sometime after returning to Cincinnati, a friend of Elizabeth’s became extremely and painfully ill with what is now believed to be uterine cancer. Concerned for her friend, Elizabeth regularly visited and nursed her. One day as they sat and talked, her friend said that it was too bad that Elizabeth wasn’t a doctor—she hated the male doctors that came to see her, since they were so cold and uncaring … a female doctor would at least have a sense of compassion.

At first, the idea of becoming a doctor revolted Elizabeth, who said that she, “hated everything connected with the body and could not bear the sight of a medical book.” The idea was almost laughable, but Elizabeth couldn’t laugh as she watched her friend dying, as she witnessed the brusque way the doctors acted towards their patients, how her father had died … and she was convinced to her core that a woman’s natural ability to be empathetic, kind and caring would warrant her to become an excellent doctor. Elizabeth resolved herself to become a doctor.

If this vow shocked her family, no one showed it, and her older sister Anna helped Elizabeth secure several more teaching jobs to help her raise the $3000 needed for tuition. When she taught music in North Carolina, Elizabeth stayed with Reverend John Dickson, who had been a doctor before becoming a minister. He was pleased that Elizabeth wanted to become a doctor and allowed her full use of all of his medical books to study from. Sometime later, Elizabeth moved in with the reverend’s brother, Dr. Samuel Henry Dickson, and he helped her write letters of application to various medical colleges in Philadelphia and New York. Wanting to go to school in Philadelphia, Elizabeth moved there and lived with Dr. William Elder and was privately tutored by Dr. Johnathan Allen. They encouraged her when other doctors dismissed her and advised her to go to Paris (where she would only be trained as a midwife) or disguise herself as a man and attend school.

Elizabeth continued to write letters, and for a very long time they continued to return rejected. It must had been indescribably infuriating to read the responses, ranging from rude to cruel. One common reason for rejection was that the faculty believed that, as a woman, Elizabeth’s brain was too inferior to a man’s, making medical study too difficult for her intellectually. Another type of response stated that they actually feared that she would be too talented as a doctor, which would encourage other women to apply and thus create competition for the male doctors. Elizabeth must have been feeling increasingly hopeless.

Then, unexpectedly, a letter arrived—Elizabeth had been accepted to the Geneva Medical College of New York! Elated, Elizabeth packed her things and moved to New York, striding proudly up to the dean of students and extending her acceptance letter … only to see the blood drain from his face. The dean spluttered, shocked; when he had gotten the application letter from Elizabeth, he hadn’t known what to do with it, so he had shown it to the faculty. The faculty in turn showed it to their all-male students, asking if they should go ahead and admit her, but if even a single student objected they wouldn’t. The students, thinking this a prank from a rival school, decided to play along and unanimously voted to admit Elizabeth …

But none of them thought she was real!

Elizabeth must have been hurt by the revelation, but when the deans and faculty discussed the matter they decided to admit her after all, likely not thinking she’d last long. The male students were flabbergasted, and a great many students and professors were rude to her—only to be frustrated as Elizabeth remained unfailingly calm and polite. When the curriculum turned to the subject of reproduction, her professor Dr. James Webster asked Elizabeth to leave the room because the terminology he would used he deemed to be too vulgar for her to hear. Unfazed, Elizabeth politely responded that she was fully ready to learn and would not have an issue with the subject. Irked, Webster then began to use words so vulgar that more than one shocked look passed around the room, but Elizabeth said nothing. She just sat there and took notes. He wasn’t going to scare her away.

Her presence had a way of turning rowdy boys into perfect gentlemen—whenever she walked into a room, the horseplay stopped and the boys sat quietly at their desk (a phenomenon that amazed their frazzled professors.) It took some time, but the young men grudgingly, admiringly began to accept Elizabeth—a few even tried to court her, though she gently turned them away. Eventually, even her professors were won over, and she received tremendous encouragement.

Still, the Geneva College was about the only place where Elizabeth was accepted as a medical student. When she went to work at area poor hospitals for experience, the resident doctors were so angry that they walked out. There were times where Elizabeth wanted to study a particular ward, and she was completely shut out. One of the few places where she was allowed to work were the syphilis and typhus wards, but Elizabeth, never daunted, worked hard and eventually used her experience and research to write about typhus as her thesis project.

Finally, after years of hard work and frustration, Elizabeth was awarded her medical degree on January 23, 1849. As Elizabeth reached to accept her diploma, dean Dr. Charles Lee stood up out of his chair and bowed appreciatively to her.

Deciding that her study was not completed, Elizabeth enrolled at La Maternite in Paris, though she was only allowed to enroll as a midwife, not a doctor. She studied hard and did so well that Dr. Paul Dubois, the world’s leading obstetrician at the time, praised her, saying that she would become the greatest obstetrician in the United States.

Unfortunately, bad luck struck Elizabeth yet again; one day while treating an infant for ophthalmia neonatorum (a severe infection of the eyes caused by chlamydia), Elizabeth accidentally sprayed some of the contaminated solution into her face. A horrific infection set in, leaving Elizabeth completely blind in her left eye. Without the ability to see, she no longer had a chance to become a surgeon.

Upon completing her training, Elizabeth realized that the anti-female doctor prejudice was much more severe in Europe than in the United States, so she returned stateside and set up her practice. At first it was difficult finding a building to rent—many realtors balked at the ides of a woman doctor, and then it was difficult to find patients. Elizabeth knew why people were so suspicious of her—the only time “female physician” had ever been applied was to women who practiced abortions, and that was likely scaring her potential patients off. (It’s also a source of the endless hate mail she received.) During this time Elizabeth met a German woman doctor named Marie Zakrzewska, and encouraged her to join Elizabeth’s practice. Soon they were joined by Elizabeth’s younger sister Emily, who had recently graduated and was now the third female doctor in the United States, and together they opened the Infirmary for Indignant Women and Children in 1857. Unlike other hospitals, Elizabeth’s hospital was completely run, funded and staffed by women, and with all their diligent work, their patient load doubled in a single year.

Things seemed to be going well, but feeling unable to sate the loneliness she felt, in 1856 Elizabeth adopted a little, orphaned Irish girl named Kitty Barry. Still motivated to do good and reform society, Elizabeth was a vocal supporter of the Civil War, seeing it as a way to end slavery. She and Emily petitioned to help the ar effort by sending several of their female doctors, but they were shocked when the United States Sanitary Commission vehemently rejected their request, choosing to employ nurses trained by Dorothea Dix, the mental health activist. Any hurt feelings were soothed in 1859 when Elizabeth was included in the British Medical Register alongside other established male doctors—she felt that it was a great honor.

1868 they added the Women’s Medical College of New York and rapidly began attracting female students. After some time, the sisters added a nursing training school to the college, which pleased Elizabeth’s friend Florence Nightingale, the famed English nurse and founder of modern nursing. Unfortunately, the friendship dissolved when Florence pressured Elizabeth to stop teaching doctors and start teaching more nurses—for the life of her, Florence didn’t see the point in teaching women to be physicians. Insulted, Elizabeth cut off all ties with Florence.

Wanting to see her success replicated overseas, Elizabeth returned to England to raise money to open another medical college there. In 1874 she opened the London School of Medicine and ran it jointly with one of her own medical students, Dr. Sophia Jex-Blake. Unfortunately, both women had strong personalities and they frequently clashed over things such as vivisection in the classrooms, to which Elizabeth was ardently opposed. The infighting weakened Elizabeth’s position until Jex-Blake gained her authority. Elizabeth remained, teaching gynecology for a short time (she was opposed to contraception and argued instead for the rhythm method) before finally retiring in 1877. She lived the rest of her life in England, writing several books on health, social reform, and her own autobiography.

In 1907, an elderly Elizabeth slipped and fell down a long flight of stairs. She was badly hurt, the injuries leaving her largely disabled. After struggling for many years, Elizabeth Blackwell died at her home at Hastings, Sussex, England following a stroke on May 31, 1910 at the age of 89. Today her memory is honored with the American Medical Woman’s Association award the Elizabeth Blackwell Medal, given to a female physician annually. Additionally, Hobart and William Smith Colleges (formerly Elizabeth’s alma mater Geneva College) gives the Elizabeth Blackwell Award to women who have committed great services to humankind. A fitting honor for a woman who has done so much to help people everywhere by opening the field of medicine to women.

Elizabeth Blackwell works referenced:

The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Women’s History, by Sonia Weiss et al 2001

Elizabeth Blackwell http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_Blackwell#cite_note-Pioneer-2

Elizabeth Blackwell http://www.notablebiographies.com/Be-Br/Blackwell-Elizabeth.html

Three Students from the Women's Medical College